What is cirrhosis?

Cirrhosis is a condition in which the liver slowly deteriorates and malfunctions due to chronic injury. Scar tissue replaces healthy liver tissue, partially blocking the flow of blood through the liver. Scarring also impairs the liver’s ability to

•control infections

•remove bacteria and toxins from the blood

•process nutrients, hormones, and drugs

•make proteins that regulate blood clotting

•produce bile to help absorb fats—including cholesterol—and fat-soluble vitamins

A healthy liver is able to regenerate most of its own cells when they become damaged. With end-stage cirrhosis, the liver can no longer effectively replace damaged cells. A healthy liver is necessary for survival.

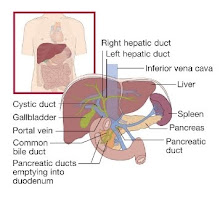

The liver and digestive system.

Cirrhosis is the twelfth leading cause of death by disease, accounting for 27,000 deaths each year.1 The condition affects men slightly more often than women.

What causes cirrhosis?

Cirrhosis has various causes. In the United States, heavy alcohol consumption and chronic hepatitis C have been the most common causes of cirrhosis. Obesity is becoming a common cause of cirrhosis, either as the sole cause or in combination with alcohol, hepatitis C, or both. Many people with cirrhosis have more than one cause of liver damage.

Cirrhosis is not caused by trauma to the liver or other acute, or short-term, causes of damage. Usually years of chronic injury are required to cause cirrhosis.

Alcohol-related liver disease.

Most people who consume alcohol do not suffer damage to the liver. But heavy alcohol use over several years can cause chronic injury to the liver. The amount of alcohol it takes to damage the liver varies greatly from person to person. For women, consuming two to three drinks—including beer and wine—per day and for men, three to four drinks per day, can lead to liver damage and cirrhosis. In the past, alcohol-related cirrhosis led to more deaths than cirrhosis due to any other cause. Deaths caused by obesity-related cirrhosis are increasing.

Chronic hepatitis C.

The hepatitis C virus is a liver infection that is spread by contact with an infected person’s blood. Chronic hepatitis C causes inflammation and damage to the liver over time that can lead to cirrhosis.

Chronic hepatitis B and D.

The hepatitis B virus is a liver infection that is spread by contact with an infected person’s blood, semen, or other body fluid. Hepatitis B, like hepatitis C, causes liver inflammation and injury that can lead to cirrhosis. The hepatitis B vaccine is given to all infants and many adults to prevent the virus. Hepatitis D is another virus that infects the liver and can lead to cirrhosis, but it occurs only in people who already have hepatitis B.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

In NAFLD, fat builds up in the liver and eventually causes cirrhosis. This increasingly common liver disease is associated with obesity, diabetes, protein malnutrition, coronary artery disease, and corticosteroid medications.

Autoimmune hepatitis.

This form of hepatitis is caused by the body’s immune system attacking liver cells and causing inflammation, damage, and eventually cirrhosis. Researchers believe genetic factors may make some people more prone to autoimmune diseases. About 70 percent of those with autoimmune hepatitis are female.

Diseases that damage or destroy bile ducts.

Several different diseases can damage or destroy the ducts that carry bile from the liver, causing bile to back up in the liver and leading to cirrhosis. In adults, the most common condition in this category is primary biliary cirrhosis, a disease in which the bile ducts become inflamed and damaged and, ultimately, disappear. Secondary biliary cirrhosis can happen if the ducts are mistakenly tied off or injured during gallbladder surgery. Primary sclerosing cholangitis is another condition that causes damage and scarring of bile ducts. In infants, damaged bile ducts are commonly caused by Alagille syndrome or biliary atresia, conditions in which the ducts are absent or injured.

Inherited diseases.

Cystic fibrosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, hemochromatosis, Wilson disease, galactosemia, and glycogen storage diseases are inherited diseases that interfere with how the liver produces, processes, and stores enzymes, proteins, metals, and other substances the body needs to function properly. Cirrhosis can result from these conditions.

Drugs, toxins, and infections.

Other causes of cirrhosis include drug reactions, prolonged exposure to toxic chemicals, parasitic infections, and repeated bouts of heart failure with liver congestion.

What are the symptoms of cirrhosis?

Many people with cirrhosis have no symptoms in the early stages of the disease. However, as the disease progresses, a person may experience the following symptoms:

•weakness

•fatigue

•loss of appetite

•nausea

•vomiting

•weight loss

•abdominal pain and bloating when fluid accumulates in the abdomen

•itching

•spiderlike blood vessels on the skin

What are the complications of cirrhosis?

As liver function deteriorates, one or more complications may develop. In some people, complications may be the first signs of the disease.

Edema and ascites. When liver damage progresses to an advanced stage, fluid collects in the legs, called edema, and in the abdomen, called ascites. Ascites can lead to bacterial peritonitis, a serious infection.

Bruising and bleeding. When the liver slows or stops producing the proteins needed for blood clotting, a person will bruise or bleed easily.

Portal hypertension. Normally, blood from the intestines and spleen is carried to the liver through the portal vein. But cirrhosis slows the normal flow of blood, which increases the pressure in the portal vein. This condition is called portal hypertension.

Esophageal varices and gastropathy. When portal hypertension occurs, it may cause enlarged blood vessels in the esophagus, called varices, or in the stomach, called gastropathy, or both. Enlarged blood vessels are more likely to burst due to thin walls and increased pressure. If they burst, serious bleeding can occur in the esophagus or upper stomach, requiring immediate medical attention.

Splenomegaly. When portal hypertension occurs, the spleen frequently enlarges and holds white blood cells and platelets, reducing the numbers of these cells in the blood. A low platelet count may be the first evidence that a person has developed cirrhosis.

Jaundice. Jaundice occurs when the diseased liver does not remove enough bilirubin from the blood, causing yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes and darkening of the urine. Bilirubin is the pigment that gives bile its reddish-yellow color.

Gallstones. If cirrhosis prevents bile from flowing freely to and from the gallbladder, the bile hardens as gallstones.

Sensitivity to medications. Cirrhosis slows the liver’s ability to filter medications from the blood. When this occurs, medications act longer than expected and build up in the body. This causes a person to be more sensitive to medications and their side effects.

Hepatic encephalopathy. A failing liver cannot remove toxins from the blood, and they eventually accumulate in the brain. The buildup of toxins in the brain—called hepatic encephalopathy—can decrease mental function and cause coma. Signs of decreased mental function include confusion, personality changes, memory loss, trouble concentrating, and a change in sleep habits.

Insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Cirrhosis causes resistance to insulin—a hormone produced by the pancreas that enables the body to use glucose as energy. With insulin resistance, the body’s muscle, fat, and liver cells do not use insulin properly. The pancreas tries to keep up with the demand for insulin by producing more, but excess glucose builds up in the bloodstream causing type 2 diabetes.

Liver cancer. Hepatocellular carcinoma is a type of liver cancer that can occur in people with cirrhosis. Hepatocellular carcinoma has a high mortality rate, but several treatment options are available.

Other problems. Cirrhosis can cause immune system dysfunction, leading to the risk of infection. Cirrhosis can also cause kidney and lung failure, known as hepatorenal and hepatopulmonary syndromes.

How is cirrhosis diagnosed?

The diagnosis of cirrhosis is usually based on the presence of a risk factor for cirrhosis, such as alcohol use or obesity, and is confirmed by physical examination, blood tests, and imaging. The doctor will ask about the person’s medical history and symptoms and perform a thorough physical examination to observe for clinical signs of the disease. For example, on abdominal examination, the liver may feel hard or enlarged with signs of ascites. The doctor will order blood tests that may be helpful in evaluating the liver and increasing the suspicion of cirrhosis.

To view the liver for signs of enlargement, reduced blood flow, or ascites, the doctor may order a computerized tomography (CT) scan, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or liver scan. The doctor may look at the liver directly by inserting a laparoscope into the abdomen. A laparoscope is an instrument with a camera that relays pictures to a computer screen.

A liver biopsy can confirm the diagnosis of cirrhosis but is not always necessary. A biopsy is usually done if the result might have an impact on treatment. The biopsy is performed with a needle inserted between the ribs or into a vein in the neck. Precautions are taken to minimize discomfort. A tiny sample of liver tissue is examined with a microscope for scarring or other signs of cirrhosis. Sometimes a cause of liver damage other than cirrhosis is found during biopsy.

How is the severity of cirrhosis measured?

The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score measures the severity of cirrhosis. The MELD score was developed to predict the 90-day survival of people with advanced cirrhosis. The MELD score is based on three blood tests:

•international normalized ratio (INR)—tests the clotting tendency of blood

•bilirubin—tests the amount of bile pigment in the blood

•creatinine—tests kidney function

MELD scores usually range between 6 and 40, with a score of 6 indicating the best likelihood of 90-day survival.

How is cirrhosis treated?

Treatment for cirrhosis depends on the cause of the disease and whether complications are present. The goals of treatment are to slow the progression of scar tissue in the liver and prevent or treat the complications of the disease. Hospitalization may be necessary for cirrhosis with complications.

Eating a nutritious diet. Because malnutrition is common in people with cirrhosis, a healthy diet is important in all stages of the disease. Health care providers recommend a meal plan that is well balanced. If ascites develops, a sodium-restricted diet is recommended. A person with cirrhosis should not eat raw shellfish, which can contain a bacterium that causes serious infection. To improve nutrition, the doctor may add a liquid supplement taken by mouth or through a nasogastric tube—a tiny tube inserted through the nose and throat that reaches into the stomach.

Avoiding alcohol and other substances. People with cirrhosis are encouraged not to consume any alcohol or illicit substances, as both will cause more liver damage. Because many vitamins and medications—prescription and over-the-counter—can affect liver function, a doctor should be consulted before taking them.

Treatment for cirrhosis also addresses specific complications. For edema and ascites, the doctor will recommend diuretics—medications that remove fluid from the body. Large amounts of ascitic fluid may be removed from the abdomen and checked for bacterial peritonitis. Oral antibiotics may be prescribed to prevent infection. Severe infection with ascites will require intravenous (IV) antibiotics.

The doctor may prescribe a beta-blocker or nitrate for portal hypertension. Beta-blockers can lower the pressure in the varices and reduce the risk of bleeding. Gastrointestinal bleeding requires an immediate upper endoscopy to look for esophageal varices. The doctor may perform a band-ligation using a special device to compress the varices and stop the bleeding. People who have had varices in the past may need to take medicine to prevent future episodes.

Hepatic encephalopathy is treated by cleansing the bowel with lactulose—a laxative given orally or in enemas. Antibiotics are added to the treatment if necessary. Patients may be asked to reduce dietary protein intake. Hepatic encephalopathy may improve as other complications of cirrhosis are controlled.

Some people with cirrhosis who develop hepatorenal failure must undergo regular hemodialysis treatment, which uses a machine to clean wastes from the blood. Medications are also given to improve blood flow through the kidneys.

Other treatments address the specific causes of cirrhosis. Treatment for cirrhosis caused by hepatitis depends on the specific type of hepatitis. For example, interferon and other antiviral drugs are prescribed for viral hepatitis, and autoimmune hepatitis requires corticosteroids and other drugs that suppress the immune system.

Medications are given to treat various symptoms of cirrhosis, such as itching and abdominal pain.

When is a liver transplant indicated for cirrhosis?

A liver transplant is considered when complications cannot be controlled by treatment. Liver transplantation is a major operation in which the diseased liver is removed and replaced with a healthy one from an organ donor. A team of health professionals determines the risks and benefits of the procedure for each patient. Survival rates have improved over the past several years because of drugs that suppress the immune system and keep it from attacking and damaging the new liver.

The number of people who need a liver transplant far exceeds the number of available organs. A person needing a transplant must go through a complicated evaluation process before being added to a long transplant waiting list. Generally, organs are given to people with the best chance of living the longest after a transplant. Survival after a transplant requires intensive follow-up and cooperation on the part of the patient and caregiver.

Points to Remember

•Cirrhosis is a condition in which the liver slowly deteriorates and malfunctions due to chronic injury. Scar tissue replaces normal, healthy liver tissue, preventing the liver from working as it should.

•In the United States, heavy alcohol consumption and chronic hepatitis C have been the most common causes of cirrhosis. Obesity is becoming a common cause of cirrhosis, either as the sole cause or in combination with alcohol, hepatitis C, or both. Many people with cirrhosis have more than one cause of liver damage.

•Other causes of cirrhosis include hepatitis B, hepatitis D, and autoimmune hepatitis; diseases that damage or destroy bile ducts, inherited diseases, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; and drugs, toxins, and infections.

•Many people with cirrhosis have no symptoms in the early stages of the disease. As the disease progresses, symptoms may include weakness, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, abdominal pain and bloating, itching, and spiderlike blood vessels on the skin.

•As liver function deteriorates, one or more complications may develop. In some people, complications may be the first signs of the disease.

•The goals of treatment are to stop the progression of scar tissue in the liver and prevent or treat complications.

•Treatment for cirrhosis includes avoidance of alcohol and other drugs, nutrition therapy, and other therapies that treat specific complications or causes of the disease.

•Hospitalization may be necessary for cirrhosis with complications.

•A liver transplant is considered when complications of cirrhosis cannot be controlled by treatment.

Hope through Research

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases’ Division of Digestive Diseases and Nutrition supports basic and clinical research into liver diseases—including cirrhosis—and liver transplantation. Researchers are also studying

•the mechanisms of cirrhosis reversal in the early stages of the disease

•potential new approaches to the management of complications of cirrhosis

•the long-term outcome of new drugs to treat portal hypertension

•the development of therapies to prevent and treat the recurrence of hepatitis C after liver transplantation

Monday, November 23, 2009

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

Alcoholic Liver Disease

Liver disease is the fourth commonest cause of death in adults between the ages of 20 and 70 years in Canada. Alcohol is still the commonest cause of chronic liver disease in this country. Not all those who abuse alcohol develop liver damage: the incidence of cirrhosis among alcoholics is approximately 10-30%. The mechanism for the predisposition of certain people to develop cirrhosis is still unknown. The amount of alcohol ingested has been shown in epidemiological studies to be the most important factor in determining the development of cirrhosis. Males drinking in excess of 80 g and females in excess of 40 g of alcohol per day for 10 years are at a high risk of developing cirrhosis. The alcohol content rather than the type of beverage is important, and binge drinking is less injurious to the liver than continued daily drinking.

Women are more susceptible to liver damage than men. They are likely to develop cirrhosis at an earlier age, present at a later stage and have more severe liver disease with more complications. Genetics may play a role in the development of alcoholic liver disease, although no single genetic marker has been identified. Patterns of alcohol drinking behavior are inherited. Alcohol is metabolized to acetaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenase and then to acetate by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. Genetic pleomorphism of the enzyme systems that metabolize alcohol, leading to different rates of alcohol elimination, also contributes to the individual's susceptibility to alcohol damage. Alcoholics with decreased acetaldehyde dehydrogenase activity develop alcoholic liver disease at a lower cumulative intake than others. Malnutrition may play a permissive role in producing alcohol hepatotoxicity. However, there is a threshold of alcohol toxicity beyond which no dietary supplements can offer protection.

The spectrum of liver disease covers the relatively benign steatosis to the potentially fatal alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis.

Alcoholic Fatty Liver page

Fatty liver is the most frequent hepatic abnormality found in alcoholics. It is a toxic manifestation of ethanol ingestion, appearing within three to seven days of excess alcohol intake. Metabolic changes associated with ethanol ingestion result in increased triglyceride synthesis, decreased lipid oxidation and impaired secretion by the liver. This results in the accumulation of triglycerides in the hepatocytes, mainly in the terminal hepatic venular zone. In more severe cases, the fatty change may be diffuse. The fat tends to accumulate as macrovesicular (large droplets), rather than microvesicular (small droplets), which represents mitochondrial damage. Fatty liver may occur alone or be part of the picture of alcoholic hepatitis or cirrhosis.

Clinically, the patient is usually asymptomatic, and the examination reveals a firm, smooth, enlarged liver. Occasionally the fatty liver may be so severe that the patient is anorexic and nauseated, and has right upper quadrant pain or discomfort. This usually follows a prolonged heavy alcoholic binge. Liver function tests including bilirubin, albumin and INR are usually normal, although the g-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) is invariably elevated while the aminotransferases and alkaline phosphatase may be slightly increased. A fatty liver is usually detected by ultrasound. Liver biopsy is required to make a definitive diagnosis. When fatty liver is not associated with alcoholic hepatitis, its prognosis is excellent. Complete abstinence from alcohol and a nutritious diet will lead to disappearance of the fat over four to six weeks.

Alcoholic Hepatitis

Alcoholic hepatitis may occur separately or in combination with cirrhosis. There are all grades of severity. It is a condition characterized by liver cell necrosis and inflammatory reaction. Histologically, hepatocytes are swollen as a result of an increase in intracellular water secondary to increase in cytosolic proteins. Steatosis, often of the macrovesicular type, is present. Alcoholic hyaline (Mallory's) bodies are purplish red intracytoplasmic inclusions consisting of clumped organelles and intermediate microfilaments. Polymorphs are seen surrounding Mallory-containing cells and also within damaged hepatocytes. Collagen deposition is usually present. It is maximal in the zone 3 and extends in a perisinusoidal pattern to enclose hepatocytes, giving it a "chicken wiring" effect. Changes in the portal triad are inconspicuous. Marked portal inflammation suggests an associated viral hepatitis such as hepatitis C, whereas fibrosis suggests complicating chronic hepatitis. When the acute inflammation settles, a varying degree of fibrosis is seen, which may eventually lead to cirrhosis.

Clinically, mild cases of alcoholic hepatitis are recognized on liver biopsy only in patients who present with a history of alcohol abuse and abnormal liver enzymes. In the moderately severe case, the patient is usually malnourished and presents with a two-to three-week prodrome of fatigue, anorexia, nausea and weight loss. Clinical signs include a fever of <40ºC, jaundice and tender hepatomegaly. In the most severe case, which usually follows a period of heavy drinking without eating, the patient is gravely ill with fever, marked jaundice, ascites, and evidence of a hyperdynamic circulation such as systemic hypotension and tachycardia. Florid palmar erythema and spider nevi are present, with or without gynecomastia. Hepatic decompensation can be precipitated by vomiting, diarrhea or intercurrent infection leading to encephalopathy. Hypoglycemia occurs often and can precipitate coma. Gastrointestinal bleeding is common, usually from a local gastric or duodenal lesion, resulting from the combination of a bleeding tendency and portal hypertension. Signs of malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies are common. Intake of moderate doses of acetaminophen in an alcoholic may precipitate florid alcoholic hepatitis.

Laboratory abnormalities include elevations of the aminotransferases, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and GGT. The aminotransferase levels rarely exceed 300 IU/L, except in association with acetaminophen ingestion; the AST/ALT ratio is usually >2. Hyperbilirubinemia can be quite marked, with levels reaching 300 to 500 µmol/L, and is a reflection of the severity of the illness. The increase in GGT is proportionally greater than that of alkaline phosphatase. There is also leukocytosis of up to 20-25 x 109/L and increased INR/prothrombin time, which does not respond to vitamin K. The serum albumin falls. Serum IgA is markedly increased, with IgG and IgM raised to a lesser extent.

Patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis often deteriorate during the first few weeks in hospital, with a mortality rate of 20-50%. Bad prognostic indicators include spontaneous encephalopathy, markedly increased INR/PT unresponsive to vitamin K and severe hyperbilirubinemia of greater than 350 µmol/L. The condition may take one to six months to resolve, even with complete abstinence. Alcoholic hepatitis progresses to cirrhosis in 25-30% of clinical episodes.

Alcoholic Cirrhosis

Established cirrhosis is usually a disease of middle age after the patient has had many years of drinking. Although there may be a history of alcoholic hepatitis, cirrhosis can develop in apparently well-nourished, asymptomatic patients. Occasionally the patient may present with end-stage liver disease with malnutrition, ascites, encephalopathy and a bleeding tendency. A history of alcohol abuse usually points to the etiology. Clinically, the patient is wasted. There may be bilateral parotid enlargement and Dupuytren's contracture in alcohol abuse. The patient may have palmar erythema and multiple spider nevi of chronic liver disease. Males develop gynecomastia and small testes. Hepatomegaly is often present, affecting predominantly the left lobe as a result of marked hypertrophy. There may be signs of portal hypertension, which include splenomegaly, ascites and distended abdominal wall veins. At the late stage, the liver may become shrunken and impalpable. There may be signs of alcohol damage in other organ systems, such as peripheral neuropathy and memory loss from cerebral atrophy. Alcoholic cirrhosis is also associated with renal problems, including IgA nephropathy, renal tubular acidosis and the development of hepatorenal syndrome. There is an association between hepatitis B and C and alcoholic cirrhosis.

Histologically, the cirrhosis is micronodular. The degree of steatosis is variable and alcoholic hepatitis may or may not be present. Pericellular fibrosis around hepatocytes is widespread. Portal fibrosis contributes to the development of portal hypertension. There may be increased parenchymal iron deposition. When parenchymal iron deposition is marked, genetic hemochromatosis has to be excluded. With continued cell necrosis and regeneration, the cirrhosis may progress to a macronodular pattern.

Biochemical abnormalities include a low serum albumin, and elevated bilirubin and aminotransferases. AST and ALT levels rarely exceed 300 IU/L and the AST/ALT ratio usually exceeds 2. GGT is disproportionately raised with recent alcohol ingestion and is a widely used screening test for alcohol abuse. With severe disease, the INR/PT may be increased. Portal hypertension results in hypersplenism leading to thrombocytopenia, anemia and leukopenia. Other nonspecific serum changes in acute and chronic alcoholics include elevations in uric acid, lactate and triglyceride, and reductions in glucose and magnesium.

The prognosis of alcoholic cirrhosis depends on whether the patient can abstain from alcohol; this in turn is related to family support, financial resources and socioeconomic state. Patients who abstain have a five-year survival rate of 60-70%, which falls to 40% in those who continue to drink. Women have a shorter survival rate than men. Bad prognostic indicators include a low serum albumin, increased INR/PT, low hemoglobin, encephalopathy, persistent jaundice and azotemia. Zone 3 fibrosis and perivenular sclerosis are also unfavorable features. Complete abstinence may not improve prognosis when portal hypertension is severe. Hepatocellular carcinoma occurs in 10% of stable cirrhotics. This usually develops after a period of abstinence when macronodular cirrhosis is present. It is usually fatal in six months.

Management

Early recognition of alcoholism is important. Physicians should have a high index of suspicion when a patient presents with anorexia, nausea, diarrhea, right upper quadrant tenderness and an elevated GGT. The most important therapeutic measure is total abstinence from alcohol. Support groups and regular follow-up can reinforce the need for abstinence. Withdrawal symptoms should be treated with chlordiazepoxide or diazepam. A nutritious, well-balanced diet with vitamin supplements should be instituted.

Alcoholic fatty liver responds to alcohol withdrawal and a nutritious diet. Patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis should be admitted to hospital and complications of liver failure treated appropriately. These patients usually have significant metabolic abnormalities that have to be corrected. Hyperglycemia is a common manifestation of chronic liver disease because of insulin resistance, whereas hypoglycemia is a manifestation of (especially fulminant) hepatic failure because of failure of gluconeogenesis and depletion of glycogen stores. Hypomagnesemia and hypokalemia are common as a result of reduced dietary intake and increased urinary excretion. Metabolic acidosis may be present, which may relate to the failure to convert lactic acid to pyruvate as well as possible underlying ketoacidosis. Specific treatments for alcoholic hepatitis include the use of corticosteroids. A recent meta-analysis of 11 controlled trials showed a significant benefit of steroids for patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis complicated by encephalopathy. Propylthiouracil has been used to dampen the hepatic hypermetabolic state in alcoholic hepatitis, and may reduce the two-year mortality rate. Testosterone and anabolic androgenic steroids have been tried with conflicting results. Intravenous amino acid supplements have been given to the severely protein malnourished with varying degrees of success. Oral supplementation is the preferred route if the patient can tolerate a diet.

Cirrhosis is an irreversible process, and therapy is directed at the complications of liver failure and portal hypertension, although colchicine has been used as an antifibrotic agent without much success. Portacaval shunts will reduce the risk of bleeding from esophageal varices, but the establishment of a shunt is associated with a 30% incidence of hepatic encephalopathy (see Section 11). Hepatic transplantation is a treatment option for patients with end-stage alcoholic cirrhosis, although the ethical issues surrounding the use of such a scarce resource for a self-inflicted disease still need to be settled. However, liver transplantation is a reasonable option in patients with alcoholic liver disease providing there is prolonged abstinence (at least six months), good social supports and no evidence of severe damage to other organs due to alcoholism. In the centers that transplant in cases of alcoholic cirrhosis, the results are comparable to those in patients with other forms of cirrhosis.

Women are more susceptible to liver damage than men. They are likely to develop cirrhosis at an earlier age, present at a later stage and have more severe liver disease with more complications. Genetics may play a role in the development of alcoholic liver disease, although no single genetic marker has been identified. Patterns of alcohol drinking behavior are inherited. Alcohol is metabolized to acetaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenase and then to acetate by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. Genetic pleomorphism of the enzyme systems that metabolize alcohol, leading to different rates of alcohol elimination, also contributes to the individual's susceptibility to alcohol damage. Alcoholics with decreased acetaldehyde dehydrogenase activity develop alcoholic liver disease at a lower cumulative intake than others. Malnutrition may play a permissive role in producing alcohol hepatotoxicity. However, there is a threshold of alcohol toxicity beyond which no dietary supplements can offer protection.

The spectrum of liver disease covers the relatively benign steatosis to the potentially fatal alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis.

Alcoholic Fatty Liver page

Fatty liver is the most frequent hepatic abnormality found in alcoholics. It is a toxic manifestation of ethanol ingestion, appearing within three to seven days of excess alcohol intake. Metabolic changes associated with ethanol ingestion result in increased triglyceride synthesis, decreased lipid oxidation and impaired secretion by the liver. This results in the accumulation of triglycerides in the hepatocytes, mainly in the terminal hepatic venular zone. In more severe cases, the fatty change may be diffuse. The fat tends to accumulate as macrovesicular (large droplets), rather than microvesicular (small droplets), which represents mitochondrial damage. Fatty liver may occur alone or be part of the picture of alcoholic hepatitis or cirrhosis.

Clinically, the patient is usually asymptomatic, and the examination reveals a firm, smooth, enlarged liver. Occasionally the fatty liver may be so severe that the patient is anorexic and nauseated, and has right upper quadrant pain or discomfort. This usually follows a prolonged heavy alcoholic binge. Liver function tests including bilirubin, albumin and INR are usually normal, although the g-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) is invariably elevated while the aminotransferases and alkaline phosphatase may be slightly increased. A fatty liver is usually detected by ultrasound. Liver biopsy is required to make a definitive diagnosis. When fatty liver is not associated with alcoholic hepatitis, its prognosis is excellent. Complete abstinence from alcohol and a nutritious diet will lead to disappearance of the fat over four to six weeks.

Alcoholic Hepatitis

Alcoholic hepatitis may occur separately or in combination with cirrhosis. There are all grades of severity. It is a condition characterized by liver cell necrosis and inflammatory reaction. Histologically, hepatocytes are swollen as a result of an increase in intracellular water secondary to increase in cytosolic proteins. Steatosis, often of the macrovesicular type, is present. Alcoholic hyaline (Mallory's) bodies are purplish red intracytoplasmic inclusions consisting of clumped organelles and intermediate microfilaments. Polymorphs are seen surrounding Mallory-containing cells and also within damaged hepatocytes. Collagen deposition is usually present. It is maximal in the zone 3 and extends in a perisinusoidal pattern to enclose hepatocytes, giving it a "chicken wiring" effect. Changes in the portal triad are inconspicuous. Marked portal inflammation suggests an associated viral hepatitis such as hepatitis C, whereas fibrosis suggests complicating chronic hepatitis. When the acute inflammation settles, a varying degree of fibrosis is seen, which may eventually lead to cirrhosis.

Clinically, mild cases of alcoholic hepatitis are recognized on liver biopsy only in patients who present with a history of alcohol abuse and abnormal liver enzymes. In the moderately severe case, the patient is usually malnourished and presents with a two-to three-week prodrome of fatigue, anorexia, nausea and weight loss. Clinical signs include a fever of <40ºC, jaundice and tender hepatomegaly. In the most severe case, which usually follows a period of heavy drinking without eating, the patient is gravely ill with fever, marked jaundice, ascites, and evidence of a hyperdynamic circulation such as systemic hypotension and tachycardia. Florid palmar erythema and spider nevi are present, with or without gynecomastia. Hepatic decompensation can be precipitated by vomiting, diarrhea or intercurrent infection leading to encephalopathy. Hypoglycemia occurs often and can precipitate coma. Gastrointestinal bleeding is common, usually from a local gastric or duodenal lesion, resulting from the combination of a bleeding tendency and portal hypertension. Signs of malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies are common. Intake of moderate doses of acetaminophen in an alcoholic may precipitate florid alcoholic hepatitis.

Laboratory abnormalities include elevations of the aminotransferases, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and GGT. The aminotransferase levels rarely exceed 300 IU/L, except in association with acetaminophen ingestion; the AST/ALT ratio is usually >2. Hyperbilirubinemia can be quite marked, with levels reaching 300 to 500 µmol/L, and is a reflection of the severity of the illness. The increase in GGT is proportionally greater than that of alkaline phosphatase. There is also leukocytosis of up to 20-25 x 109/L and increased INR/prothrombin time, which does not respond to vitamin K. The serum albumin falls. Serum IgA is markedly increased, with IgG and IgM raised to a lesser extent.

Patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis often deteriorate during the first few weeks in hospital, with a mortality rate of 20-50%. Bad prognostic indicators include spontaneous encephalopathy, markedly increased INR/PT unresponsive to vitamin K and severe hyperbilirubinemia of greater than 350 µmol/L. The condition may take one to six months to resolve, even with complete abstinence. Alcoholic hepatitis progresses to cirrhosis in 25-30% of clinical episodes.

Alcoholic Cirrhosis

Established cirrhosis is usually a disease of middle age after the patient has had many years of drinking. Although there may be a history of alcoholic hepatitis, cirrhosis can develop in apparently well-nourished, asymptomatic patients. Occasionally the patient may present with end-stage liver disease with malnutrition, ascites, encephalopathy and a bleeding tendency. A history of alcohol abuse usually points to the etiology. Clinically, the patient is wasted. There may be bilateral parotid enlargement and Dupuytren's contracture in alcohol abuse. The patient may have palmar erythema and multiple spider nevi of chronic liver disease. Males develop gynecomastia and small testes. Hepatomegaly is often present, affecting predominantly the left lobe as a result of marked hypertrophy. There may be signs of portal hypertension, which include splenomegaly, ascites and distended abdominal wall veins. At the late stage, the liver may become shrunken and impalpable. There may be signs of alcohol damage in other organ systems, such as peripheral neuropathy and memory loss from cerebral atrophy. Alcoholic cirrhosis is also associated with renal problems, including IgA nephropathy, renal tubular acidosis and the development of hepatorenal syndrome. There is an association between hepatitis B and C and alcoholic cirrhosis.

Histologically, the cirrhosis is micronodular. The degree of steatosis is variable and alcoholic hepatitis may or may not be present. Pericellular fibrosis around hepatocytes is widespread. Portal fibrosis contributes to the development of portal hypertension. There may be increased parenchymal iron deposition. When parenchymal iron deposition is marked, genetic hemochromatosis has to be excluded. With continued cell necrosis and regeneration, the cirrhosis may progress to a macronodular pattern.

Biochemical abnormalities include a low serum albumin, and elevated bilirubin and aminotransferases. AST and ALT levels rarely exceed 300 IU/L and the AST/ALT ratio usually exceeds 2. GGT is disproportionately raised with recent alcohol ingestion and is a widely used screening test for alcohol abuse. With severe disease, the INR/PT may be increased. Portal hypertension results in hypersplenism leading to thrombocytopenia, anemia and leukopenia. Other nonspecific serum changes in acute and chronic alcoholics include elevations in uric acid, lactate and triglyceride, and reductions in glucose and magnesium.

The prognosis of alcoholic cirrhosis depends on whether the patient can abstain from alcohol; this in turn is related to family support, financial resources and socioeconomic state. Patients who abstain have a five-year survival rate of 60-70%, which falls to 40% in those who continue to drink. Women have a shorter survival rate than men. Bad prognostic indicators include a low serum albumin, increased INR/PT, low hemoglobin, encephalopathy, persistent jaundice and azotemia. Zone 3 fibrosis and perivenular sclerosis are also unfavorable features. Complete abstinence may not improve prognosis when portal hypertension is severe. Hepatocellular carcinoma occurs in 10% of stable cirrhotics. This usually develops after a period of abstinence when macronodular cirrhosis is present. It is usually fatal in six months.

Management

Early recognition of alcoholism is important. Physicians should have a high index of suspicion when a patient presents with anorexia, nausea, diarrhea, right upper quadrant tenderness and an elevated GGT. The most important therapeutic measure is total abstinence from alcohol. Support groups and regular follow-up can reinforce the need for abstinence. Withdrawal symptoms should be treated with chlordiazepoxide or diazepam. A nutritious, well-balanced diet with vitamin supplements should be instituted.

Alcoholic fatty liver responds to alcohol withdrawal and a nutritious diet. Patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis should be admitted to hospital and complications of liver failure treated appropriately. These patients usually have significant metabolic abnormalities that have to be corrected. Hyperglycemia is a common manifestation of chronic liver disease because of insulin resistance, whereas hypoglycemia is a manifestation of (especially fulminant) hepatic failure because of failure of gluconeogenesis and depletion of glycogen stores. Hypomagnesemia and hypokalemia are common as a result of reduced dietary intake and increased urinary excretion. Metabolic acidosis may be present, which may relate to the failure to convert lactic acid to pyruvate as well as possible underlying ketoacidosis. Specific treatments for alcoholic hepatitis include the use of corticosteroids. A recent meta-analysis of 11 controlled trials showed a significant benefit of steroids for patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis complicated by encephalopathy. Propylthiouracil has been used to dampen the hepatic hypermetabolic state in alcoholic hepatitis, and may reduce the two-year mortality rate. Testosterone and anabolic androgenic steroids have been tried with conflicting results. Intravenous amino acid supplements have been given to the severely protein malnourished with varying degrees of success. Oral supplementation is the preferred route if the patient can tolerate a diet.

Cirrhosis is an irreversible process, and therapy is directed at the complications of liver failure and portal hypertension, although colchicine has been used as an antifibrotic agent without much success. Portacaval shunts will reduce the risk of bleeding from esophageal varices, but the establishment of a shunt is associated with a 30% incidence of hepatic encephalopathy (see Section 11). Hepatic transplantation is a treatment option for patients with end-stage alcoholic cirrhosis, although the ethical issues surrounding the use of such a scarce resource for a self-inflicted disease still need to be settled. However, liver transplantation is a reasonable option in patients with alcoholic liver disease providing there is prolonged abstinence (at least six months), good social supports and no evidence of severe damage to other organs due to alcoholism. In the centers that transplant in cases of alcoholic cirrhosis, the results are comparable to those in patients with other forms of cirrhosis.

Alcoholic Hepatitis

The liver is a marvelously sophisticated chemical laboratory, capable of carrying out thousands of chemical transformations on which the body depends. The liver produces some important chemicals from scratch and modifies others to allow the body to use them better. In addition, the liver neutralizes an enormous range of toxins. Without a functioning liver, you cannot live for long.

Unfortunately, a number of influences can severely damage the liver, of which alcohol is the most common. This powerful liver toxin harms the liver in three stages: alcoholic fatty liver, alcoholic hepatitis, then cirrhosis. Although the first two stages of injury are usually reversible, cirrhosis is not. Generally, liver cirrhosis is a result of more than 10 years of heavy alcohol abuse.

Usually, alcoholic hepatitis is discovered through blood tests that detect levels of enzymes released from the liver. The blood levels of these enzymes—known by acronyms such as SGOT, SGPT, ALT, AST, and GGT—rise as damage to the liver (by any cause) progresses.

If blood tests show that you have alcoholic hepatitis (or any other form of liver disease), it is essential that you stop drinking. There is little in the way of specific treatment beyond this.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Principle Proposed Natural Treatments

Several herbs and supplements have shown promise for protecting the liver from alcohol-induced damage. However, none of these has been conclusively proven effective, and cutting down (or eliminating) alcohol consumption is undoubtedly more effective than any other treatment. For information regarding natural treatments that can help people stop drinking, see the article on alcoholism. The alcoholism article also discusses the depletion of certain nutrients, which may affect people who consume enough alcohol to damage the liver.

Below, we concentrate on treatments used specifically to treat early liver damage caused by alcohol. Treatments for more advanced alcohol-induced liver damage are discussed in the liver cirrhosis article.

Milk Thistle

Numerous double-blind, placebo-controlled studies enrolling a total of several hundred people have evaluated whether the herb milk thistle can successfully counter alcohol-induced liver damage. However, these studies have yielded inconsistent results. For example, a double-blind, placebo-controlled study performed in 1981 followed 106 Finnish soldiers with alcoholic liver disease over a period of 4 weeks.1 The treated group showed a significant decrease in elevated liver enzymes and improvement in liver structure as evaluated by biopsy in 29 subjects.

Two similar studies enrolling a total of approximately 60 people also found benefits.2,3 However, a 3-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 116 people showed little to no additional benefit, perhaps because most participants reduced their alcohol consumption and almost half of them stopped drinking entirely.4 Another study found no benefit in 72 patients who were followed for 15 months.5

A 2007 review of published and unpublished studies on milk thistle as a treatment for liver disease concluded that benefits were seen only in low-quality trials, and, even in those, milk thistle did not show more than a slight benefit.17 And, a subsequent 2008 review of 19 randomized trials drew a similar conclusion for alcoholic liver disease generally, although it did find a modest reduction in mortality for patients with severe liver cirrhosis.18

For more information, including dosage and safety issues, see the full Milk Thistle article.

Other Proposed Natural Treatments

The supplement SAMe has also shown some promise for preventing or treating alcoholic hepatitis, but as yet there is no reliable evidence to support its use for this purpose.6-9

The supplement TMG helps the body create its own SAMe and has also shown promise in very preliminary studies.10-13

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Herbs and Supplements to Avoid

High doses of the supplements beta-carotene and vitamin A might cause alcoholic liver disease to develop more rapidly in people who abuse alcohol.14,15 Nutritional supplementation at the standard daily requirement level should not cause a problem. See the articles on Vitamin A and Beta-carotene for more information.

Although one animal study suggests that the herb kava might aid in alcohol withdrawal,16 the herb can cause liver damage; therefore, it should not be used by people with alcoholic liver disease (and probably not by anyone at all). Numerous other herbs possess known or suspected liver-toxic properties, including coltsfoot, comfrey, germander, greater celandine, kombucha, pennyroyal, and various prepackaged Chinese herbal remedies. For this reason, people with alcoholic liver disease should use caution before taking any medicinal herbs.

Unfortunately, a number of influences can severely damage the liver, of which alcohol is the most common. This powerful liver toxin harms the liver in three stages: alcoholic fatty liver, alcoholic hepatitis, then cirrhosis. Although the first two stages of injury are usually reversible, cirrhosis is not. Generally, liver cirrhosis is a result of more than 10 years of heavy alcohol abuse.

Usually, alcoholic hepatitis is discovered through blood tests that detect levels of enzymes released from the liver. The blood levels of these enzymes—known by acronyms such as SGOT, SGPT, ALT, AST, and GGT—rise as damage to the liver (by any cause) progresses.

If blood tests show that you have alcoholic hepatitis (or any other form of liver disease), it is essential that you stop drinking. There is little in the way of specific treatment beyond this.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Principle Proposed Natural Treatments

Several herbs and supplements have shown promise for protecting the liver from alcohol-induced damage. However, none of these has been conclusively proven effective, and cutting down (or eliminating) alcohol consumption is undoubtedly more effective than any other treatment. For information regarding natural treatments that can help people stop drinking, see the article on alcoholism. The alcoholism article also discusses the depletion of certain nutrients, which may affect people who consume enough alcohol to damage the liver.

Below, we concentrate on treatments used specifically to treat early liver damage caused by alcohol. Treatments for more advanced alcohol-induced liver damage are discussed in the liver cirrhosis article.

Milk Thistle

Numerous double-blind, placebo-controlled studies enrolling a total of several hundred people have evaluated whether the herb milk thistle can successfully counter alcohol-induced liver damage. However, these studies have yielded inconsistent results. For example, a double-blind, placebo-controlled study performed in 1981 followed 106 Finnish soldiers with alcoholic liver disease over a period of 4 weeks.1 The treated group showed a significant decrease in elevated liver enzymes and improvement in liver structure as evaluated by biopsy in 29 subjects.

Two similar studies enrolling a total of approximately 60 people also found benefits.2,3 However, a 3-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 116 people showed little to no additional benefit, perhaps because most participants reduced their alcohol consumption and almost half of them stopped drinking entirely.4 Another study found no benefit in 72 patients who were followed for 15 months.5

A 2007 review of published and unpublished studies on milk thistle as a treatment for liver disease concluded that benefits were seen only in low-quality trials, and, even in those, milk thistle did not show more than a slight benefit.17 And, a subsequent 2008 review of 19 randomized trials drew a similar conclusion for alcoholic liver disease generally, although it did find a modest reduction in mortality for patients with severe liver cirrhosis.18

For more information, including dosage and safety issues, see the full Milk Thistle article.

Other Proposed Natural Treatments

The supplement SAMe has also shown some promise for preventing or treating alcoholic hepatitis, but as yet there is no reliable evidence to support its use for this purpose.6-9

The supplement TMG helps the body create its own SAMe and has also shown promise in very preliminary studies.10-13

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Herbs and Supplements to Avoid

High doses of the supplements beta-carotene and vitamin A might cause alcoholic liver disease to develop more rapidly in people who abuse alcohol.14,15 Nutritional supplementation at the standard daily requirement level should not cause a problem. See the articles on Vitamin A and Beta-carotene for more information.

Although one animal study suggests that the herb kava might aid in alcohol withdrawal,16 the herb can cause liver damage; therefore, it should not be used by people with alcoholic liver disease (and probably not by anyone at all). Numerous other herbs possess known or suspected liver-toxic properties, including coltsfoot, comfrey, germander, greater celandine, kombucha, pennyroyal, and various prepackaged Chinese herbal remedies. For this reason, people with alcoholic liver disease should use caution before taking any medicinal herbs.

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

Vitamins for Healthy Liver

The liver is the central processing center for vitamins and minerals in the body. It helps you absorb the nutrients in food and it aids in the digestion of proteins, carbohydrates and fats. The liver is helped more by what you avoid than by what you take in, but there are several vitamins and minerals that can contribute to liver health.

A healthy liver is essential for the body to function properly. The liver is the filtration system of the body and is partially responsible for the distribution of minerals and vitamins throughout the rest of the body. If the liver is not healthy, or is otherwise not functioning properly, a person may have issues with the absorption of vitamins and minerals. Overall, what you avoid taking into your body affects the liver the most, but there are vitamins that will help it function at an optimum level.

Vitamins and Minerals to Use

Vitamin A is linked to the prevention of your liver accumulating tough, fibrous tissue that is characteristic of a disease. A diet rich in vitamin A can help to reduce damage in a diseased liver. If you take in too much of the vitamin, however, it may cause disease and liver enlargement. A University of Turin study showed that vitamin E may prevent against cirrhosis and liver damage. The vitamin may provide protection by reducing the spreading of lipid oxidation processes and limiting the damage that the oxidation causes. Beta carotene's contributions are twofold, healing a deficiency that may occur in liver damage and attacking free radicals that may cause liver damage in the first place. The liver uses low-density lipoproteins to remove fat fragments, but it cannot send out these fragments when there is a deficiency of choline. Lecithin supplementation, which raises blood choline levels, can take care of this problem. There is also speculation that B-vitamins, vitamin C, and vitamin D can help the liver when given in normal doses.

Vitamins and Minerals to Limit

Since the liver processes all nutrients in the body, an abundance of any vitamin over the recommended amount has the potential of causing problems. Vitamin K in large doses may produce jaundice, a disease related to the liver. Sustained released vitamins that contain niacin have been said to be hepatoxic by researchers at VCU. Biotin may cause enlargement of the liver when taken in large amounts over long periods of time. Also, there are many herbs that can cause problems in the liver. If you have liver problems or are considering taking the following herbs, consult your doctor before using: black cohosh, chaparral, ma-huang, comfrey, greater celadine, germander, kava, pennyroyal, mistletoe, valerian and skullcap.

Other Liver Tips

Avoid using alcohol to excess as it makes your liver overwork and can lead to great damage. Don't combine medications with alcohol of any kind. Try to stay away from environmental pollutants like aerosol sprays, paint thinner and bug sprays. Also, eat a healthy and balanced diet to ensure that your liver is not receiving too much or too little of anything at all.

Vitamin A

When taken in the recommended daily amounts, vitamin A helps stop the tissue of the liver from developing a rough fiber-like texture. A liver which has this texture is often unhealthy and is characteristically a sign of disease.

Foods rich in vitamin A include liver, eggs, butter, milk, cheese and other dairy products. In addition, many vegetables contain high levels of vitamin A.

Vitamin E

Vitamin E consumption has been found to lower the possibility of a person developing liver damage and cirrhosis of the liver. Vitamin E does this by slowing down the oxidation of lipids in the body. Beta caratine has been found to attack the free radicals in the body that can produce liver damage. Beta caratine also helps the body produce the necessary amounts of choline to aid in the removal of fragments of fat.

Avoiding Alcohol and Other Pollutants

Do not use alcohol in excess as it can lead to the development of liver disease as well as cirrhosis of the liver. Taking medications in combination with alcohol will cause damage to the liver and doing so should be avoided. Whenever possible, stay away from man-made and chemical pollutants as they contain free radicals which can damage your liver as well as other organs in he body.

Vitamins To Limit

There are vitamins which, if consumed in excess, have the potential to cause to damage to the liver. For instance, if vitamin K is consumed in excessive amounts it may cause jaundice, which is a disease that occurs in part from having an unhealthy liver. Some researchers also report that vitamins which contain high levels of niacin can be toxic to the liver as well.

Considerations

Maintaining a healthy liver means maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Exercise, a balanced diet, and other health conscious decisions will leave you with a happy and healthy liver. Avoid consuming any vitamin in excess and make sure to limit consumption of other things that are known to be harmful to your health. Before making any major changes to your diet, consider consulting a medical professional such as a nutritionist.

A healthy liver is essential for the body to function properly. The liver is the filtration system of the body and is partially responsible for the distribution of minerals and vitamins throughout the rest of the body. If the liver is not healthy, or is otherwise not functioning properly, a person may have issues with the absorption of vitamins and minerals. Overall, what you avoid taking into your body affects the liver the most, but there are vitamins that will help it function at an optimum level.

Vitamins and Minerals to Use

Vitamin A is linked to the prevention of your liver accumulating tough, fibrous tissue that is characteristic of a disease. A diet rich in vitamin A can help to reduce damage in a diseased liver. If you take in too much of the vitamin, however, it may cause disease and liver enlargement. A University of Turin study showed that vitamin E may prevent against cirrhosis and liver damage. The vitamin may provide protection by reducing the spreading of lipid oxidation processes and limiting the damage that the oxidation causes. Beta carotene's contributions are twofold, healing a deficiency that may occur in liver damage and attacking free radicals that may cause liver damage in the first place. The liver uses low-density lipoproteins to remove fat fragments, but it cannot send out these fragments when there is a deficiency of choline. Lecithin supplementation, which raises blood choline levels, can take care of this problem. There is also speculation that B-vitamins, vitamin C, and vitamin D can help the liver when given in normal doses.

Vitamins and Minerals to Limit

Since the liver processes all nutrients in the body, an abundance of any vitamin over the recommended amount has the potential of causing problems. Vitamin K in large doses may produce jaundice, a disease related to the liver. Sustained released vitamins that contain niacin have been said to be hepatoxic by researchers at VCU. Biotin may cause enlargement of the liver when taken in large amounts over long periods of time. Also, there are many herbs that can cause problems in the liver. If you have liver problems or are considering taking the following herbs, consult your doctor before using: black cohosh, chaparral, ma-huang, comfrey, greater celadine, germander, kava, pennyroyal, mistletoe, valerian and skullcap.

Other Liver Tips

Avoid using alcohol to excess as it makes your liver overwork and can lead to great damage. Don't combine medications with alcohol of any kind. Try to stay away from environmental pollutants like aerosol sprays, paint thinner and bug sprays. Also, eat a healthy and balanced diet to ensure that your liver is not receiving too much or too little of anything at all.

Vitamin A

When taken in the recommended daily amounts, vitamin A helps stop the tissue of the liver from developing a rough fiber-like texture. A liver which has this texture is often unhealthy and is characteristically a sign of disease.

Foods rich in vitamin A include liver, eggs, butter, milk, cheese and other dairy products. In addition, many vegetables contain high levels of vitamin A.

Vitamin E

Vitamin E consumption has been found to lower the possibility of a person developing liver damage and cirrhosis of the liver. Vitamin E does this by slowing down the oxidation of lipids in the body. Beta caratine has been found to attack the free radicals in the body that can produce liver damage. Beta caratine also helps the body produce the necessary amounts of choline to aid in the removal of fragments of fat.

Avoiding Alcohol and Other Pollutants

Do not use alcohol in excess as it can lead to the development of liver disease as well as cirrhosis of the liver. Taking medications in combination with alcohol will cause damage to the liver and doing so should be avoided. Whenever possible, stay away from man-made and chemical pollutants as they contain free radicals which can damage your liver as well as other organs in he body.

Vitamins To Limit

There are vitamins which, if consumed in excess, have the potential to cause to damage to the liver. For instance, if vitamin K is consumed in excessive amounts it may cause jaundice, which is a disease that occurs in part from having an unhealthy liver. Some researchers also report that vitamins which contain high levels of niacin can be toxic to the liver as well.

Considerations

Maintaining a healthy liver means maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Exercise, a balanced diet, and other health conscious decisions will leave you with a happy and healthy liver. Avoid consuming any vitamin in excess and make sure to limit consumption of other things that are known to be harmful to your health. Before making any major changes to your diet, consider consulting a medical professional such as a nutritionist.

Liver problems

Definition

Liver problems include a wide range of diseases and conditions that can affect your liver. Your liver is an organ about the size of a football that sits just under your rib cage on the right side of your abdomen. Without your liver, you couldn't digest food and absorb nutrients, get rid of toxic substances from your body or stay alive.

Liver problems can be inherited, or liver problems can occur in response to viruses and chemicals. Some liver problems are temporary and go away on their own, while other liver problems can last for a long time and lead to serious complications

Common Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of liver problems include:

■Discolored skin and eyes that appear yellowish

■Abdominal pain and swelling

■Itchy skin that doesn't seem to go away

■Dark urine color

■Pale stool color

■Bloody or tar-colored stool

■Chronic fatigue

■Nausea

■Loss of appetite

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your doctor if you have any persistent signs or symptoms that worry you. Seek immediate medical attention if you have abdominal pain that is so severe that you can't stay still.

Liver problems include a wide range of diseases and conditions that can affect your liver. Your liver is an organ about the size of a football that sits just under your rib cage on the right side of your abdomen. Without your liver, you couldn't digest food and absorb nutrients, get rid of toxic substances from your body or stay alive.

Liver problems can be inherited, or liver problems can occur in response to viruses and chemicals. Some liver problems are temporary and go away on their own, while other liver problems can last for a long time and lead to serious complications

Common Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of liver problems include:

■Discolored skin and eyes that appear yellowish

■Abdominal pain and swelling

■Itchy skin that doesn't seem to go away

■Dark urine color

■Pale stool color

■Bloody or tar-colored stool

■Chronic fatigue

■Nausea

■Loss of appetite

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your doctor if you have any persistent signs or symptoms that worry you. Seek immediate medical attention if you have abdominal pain that is so severe that you can't stay still.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Definition

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a term used to describe the accumulation of fat in the liver of people who drink little or no alcohol.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is common and, for most people, causes no signs and symptoms and no complications. But in some people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, the fat that accumulates can cause inflammation and scarring in the liver. This more serious form of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is sometimes called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. At its most severe, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease can progress to liver failure.

Symptoms

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease usually causes no signs and symptoms. When it does, they may include:

■Fatigue

■Pain the upper right abdomen

■Weight loss

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your doctor if you have persistent signs and symptoms.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a term used to describe the accumulation of fat in the liver of people who drink little or no alcohol.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is common and, for most people, causes no signs and symptoms and no complications. But in some people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, the fat that accumulates can cause inflammation and scarring in the liver. This more serious form of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is sometimes called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. At its most severe, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease can progress to liver failure.

Symptoms

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease usually causes no signs and symptoms. When it does, they may include:

■Fatigue

■Pain the upper right abdomen

■Weight loss

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your doctor if you have persistent signs and symptoms.

Fatty Liver

Definition of Fatty Liver

Fatty liver is the accumulation of fat in liver cells. It is also called steatosis.

Description of Fatty Liver

Possible explanations of fatty liver include the transfer of fat from other parts of the body or an increase in the extraction of fat presented to the liver from the intestine. Other explanations are that the liver reduces the rate it breaks down and removes fat. Eating fatty foods does not by itself produce a fatty liver.

Causes and Risk Factors of Fatty Liver

Alcohol, obesity, starvation, diabetes mellitus, corticosteroids, poisons (carbon tetrachloride and yellow phosphorus), Cushing's syndrome, and hyperlipidemia are some causes of fatty liver. Microvesicular fatty liver may be caused by valproic acid toxicity and high-dose tetracycline or during pregnancy.

Symptoms of Fatty Liver

Patients are often asymptomatic.

Diagnosis of Fatty Liver

The patient may have an enlarged liver or minor elevation of liver enzyme tests. Several studies show that fatty liver is one of the most common causes of isolated minor elevation of liver enzymes found in routine blood screening.

Images of the liver obtained by an ultrasound test, CT (computed tomography) scan, or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) may suggest the presence of a fatty liver. To be certain whether a patient has fatty liver requires a liver biopsy, in which a small sample of liver tissue is obtained through the skin and analyzed under the microscope.

Treatment of Fatty Liver

The treatment of fatty liver is related to the cause. It is important to remember that simple fatty liver may not require treatment. The benefit of weight loss, dietary fat restriction, and exercise in obese patients is inconsistent.

Reducing or eliminating alcohol use can improve fatty liver due to alcohol toxicity. Controlling blood sugar may reduce the severity of fatty liver in patients with diabetes. Ursodeoxycholic acid may improve liver function test results, but its effect on improving the underlying liver abnormality is unclear.

Questions To Ask Your Doctor About Fatty Liver

Is there fatty infiltration of the liver?

What did the liver function test show?

Is this related to diabetes mellitus?

Is it related to any other medical problem?

Should alcohol consumption be curtailed?

What treatment, if any, do you recommend?

Fatty liver is the accumulation of fat in liver cells. It is also called steatosis.

Description of Fatty Liver

Possible explanations of fatty liver include the transfer of fat from other parts of the body or an increase in the extraction of fat presented to the liver from the intestine. Other explanations are that the liver reduces the rate it breaks down and removes fat. Eating fatty foods does not by itself produce a fatty liver.

Causes and Risk Factors of Fatty Liver

Alcohol, obesity, starvation, diabetes mellitus, corticosteroids, poisons (carbon tetrachloride and yellow phosphorus), Cushing's syndrome, and hyperlipidemia are some causes of fatty liver. Microvesicular fatty liver may be caused by valproic acid toxicity and high-dose tetracycline or during pregnancy.

Symptoms of Fatty Liver

Patients are often asymptomatic.

Diagnosis of Fatty Liver

The patient may have an enlarged liver or minor elevation of liver enzyme tests. Several studies show that fatty liver is one of the most common causes of isolated minor elevation of liver enzymes found in routine blood screening.

Images of the liver obtained by an ultrasound test, CT (computed tomography) scan, or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) may suggest the presence of a fatty liver. To be certain whether a patient has fatty liver requires a liver biopsy, in which a small sample of liver tissue is obtained through the skin and analyzed under the microscope.

Treatment of Fatty Liver

The treatment of fatty liver is related to the cause. It is important to remember that simple fatty liver may not require treatment. The benefit of weight loss, dietary fat restriction, and exercise in obese patients is inconsistent.

Reducing or eliminating alcohol use can improve fatty liver due to alcohol toxicity. Controlling blood sugar may reduce the severity of fatty liver in patients with diabetes. Ursodeoxycholic acid may improve liver function test results, but its effect on improving the underlying liver abnormality is unclear.

Questions To Ask Your Doctor About Fatty Liver

Is there fatty infiltration of the liver?

What did the liver function test show?

Is this related to diabetes mellitus?

Is it related to any other medical problem?

Should alcohol consumption be curtailed?

What treatment, if any, do you recommend?